OKR Framework

What is the OKR Framework?

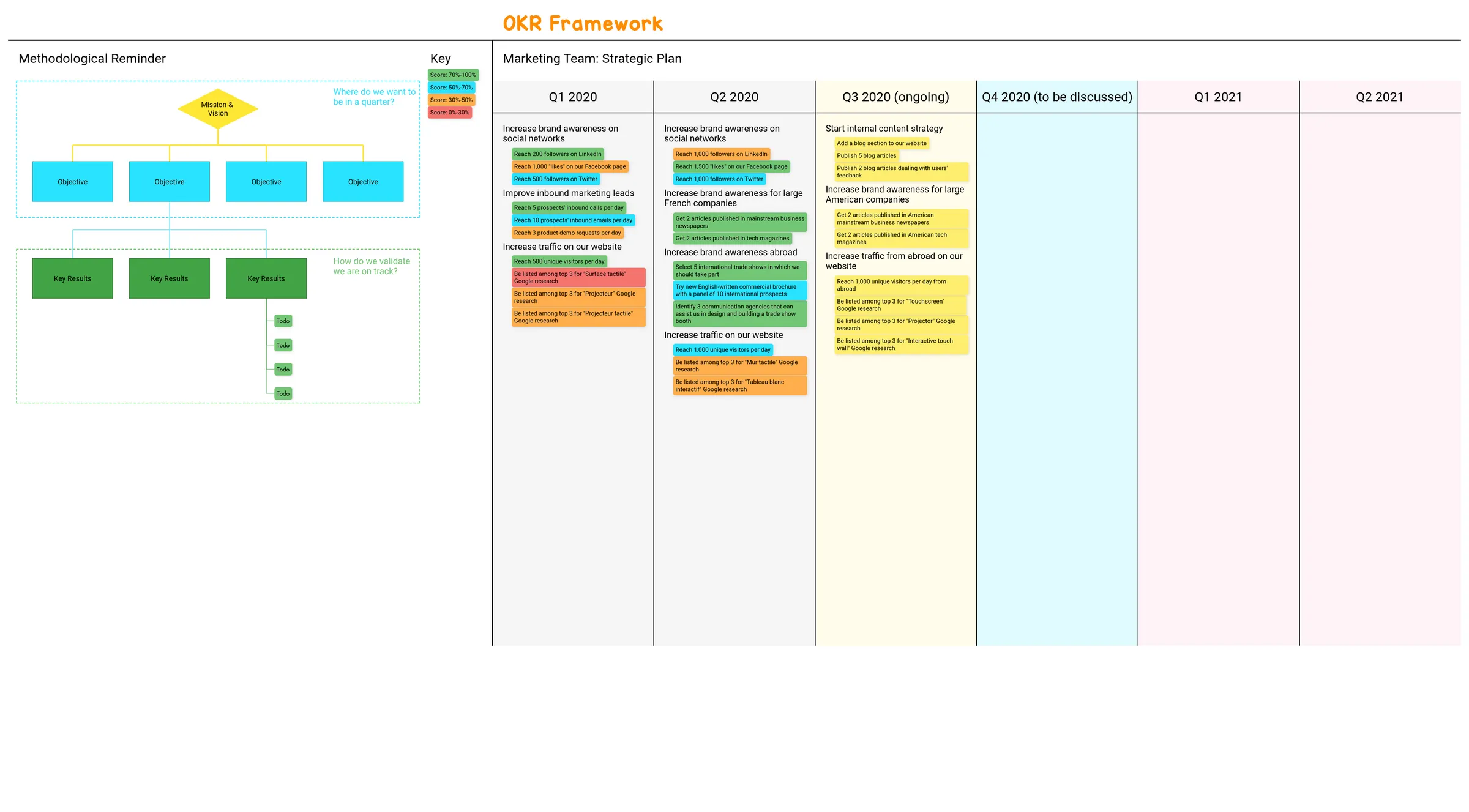

Made popular in 2013 by Rick Klau, Partner at Google Ventures Startup Lab, in Startup Lab workshop: How Google sets goals: OKRs, the OKR Framework—which stands for Objectives and Key Results—was actually first developed by Andy Grove, the CEO of Intel Corporation from 1987 to 1998. It was then passed onto Google’s founders by former Intel employee-turned venture capitalist John Doerr.

In “Objectives and Key Results: Driving Focus, Alignment, and Engagement with OKRs,” OKRs are defined as “a critical thinking framework and ongoing discipline that seeks to ensure employees work together, focusing their efforts to make measurable contributions that drive the company forward.” In other words, OKRs make goals visible and the key results that show the progress made in achieving those goals measurable.

Initially inspired by Peter Drucker’s Management by Objectives system, the OKR Framework was later simplified to answer two fundamental goal-related questions:

- What do you want to achieve? (the objective)

- How will you measure progress towards achieving that goal? (the key result)

To look at it another way, an objective describes a broad (yet achievable) qualitative short-term goal, while key results measure incremental progress towards goal completion. Generally speaking, you should have two to five key results linked to each objective.

The OKR Framework should be revisited every three months. At the end of a quarter, for example, it’s used to both evaluate achievement against current goals and then also identify new objectives and key results for the quarter ahead.

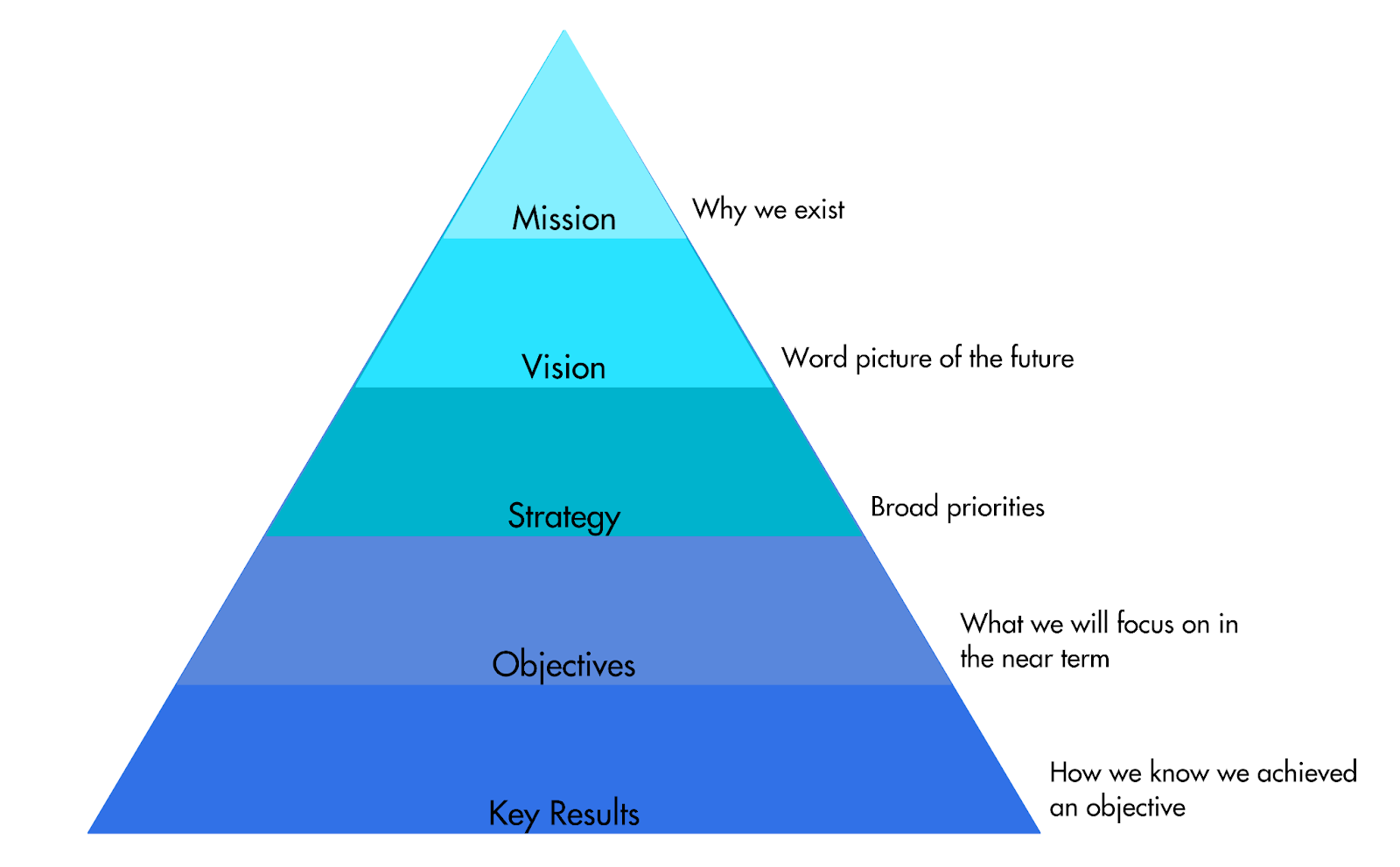

Context for OKRs

Behind the OKR Framework sits a people management strategy called “Management by Intent.” Instead of simply telling employees how to achieve specific goals, the slight nuance here is to communicate what you want them to achieve and then give them space and freedom to find a way of doing it on their own.

How to roll out the OKR Framework in your organization successfully?

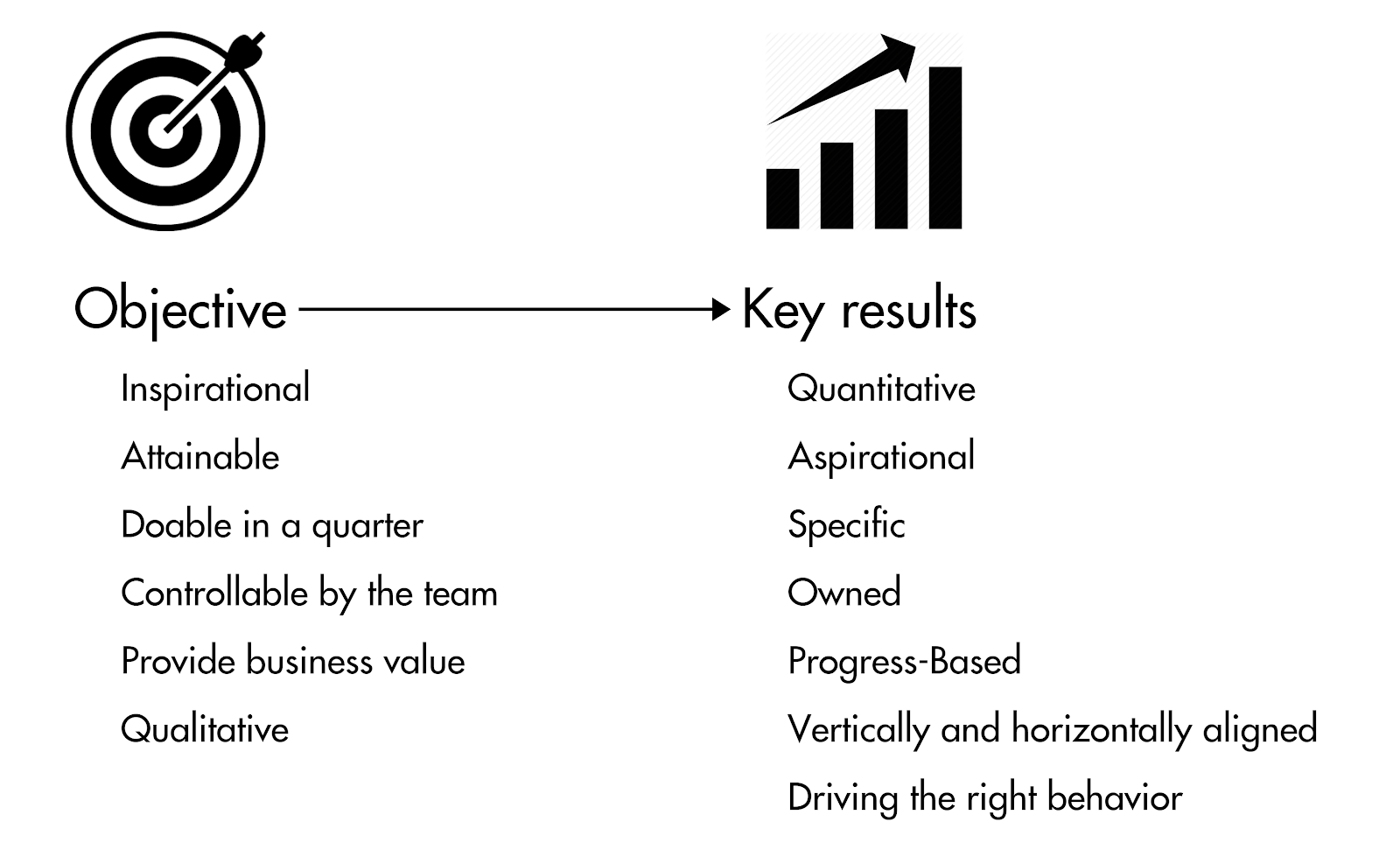

For starters, building a strong objective comes down to a few key criteria:

- Is it inspirational? The objective must engage a team in achieving something that’s bigger than just running the business as usual.

- Is it attainable? Although there’s a lot of value in setting ‘stretch goals,’ in this context it can be counterproductive if you start by setting the bar too high.

- Is it doable in a quarter? Knowing that conversations around OKRs take place every quarter, it’s important for the objectives you set to be achievable within a three-month timeframe. Anything longer is a sign that you should probably break up a big, long-term objective into small parts.

- Is it controllable by the team? When setting objectives for either a team or an individual employee, whoever is ultimately responsible for making progress against those objectives must be able to both control the outcome and also have access to all the tools necessary to achieve it within the specified timeframe.

- Does it provide business value? While this may seem obvious at face value, it’s important to ask what tangible business value will result from achieving a specific objective—or, more importantly, if a stated objective even aligns to broader business goals in the first place. This is critical for ensuring that teams don’t waste time working on goals that don’t ladder up to key business priorities.

- Is it qualitative? More often than not, objectives should never include numbers or metrics of any kind. But there can be exceptions here.

Similarly, key results have some criteria to adhere to as well:

- Are they quantitative? As opposed to objectives, key results need to be measurable and, thus, should be characterized by numbers or key metrics whenever possible.

- Are they aspirational? Key results need to be ambitious yet attainable in order to foster the right level of motivation and energy across a team.

- Are they specific: Key results must avoid ambiguity at all costs to ensure that everyone, both within and outside of a team, has a clear understanding of what success looks like upon goal completion.

- Are they owned? Even if broader goals are inspired by company senior leadership, each team must take ownership of their own key results. This is critical for how they’ll measure success as it relates to their part in achieving business objectives.

- Are they progress-based? Knowing that some objectives may involve a few ‘moving parts’ to be achieved, be sure to identify key results that can be measured frequently—say, every two weeks—to better track progress over time.

- Are they vertically and horizontally aligned? It’s important for key results to be reviewed by both senior business leaders and other cross-functional teams to ensure 100% alignment at the organizational level around what success looks like.

- Are they driving the right behaviors? Before getting too far along in the process, it’s important to ask whether the key results you choose for measuring success against specific objectives could lead to bad, unethical, or unnecessarily competitive behaviors among team members.

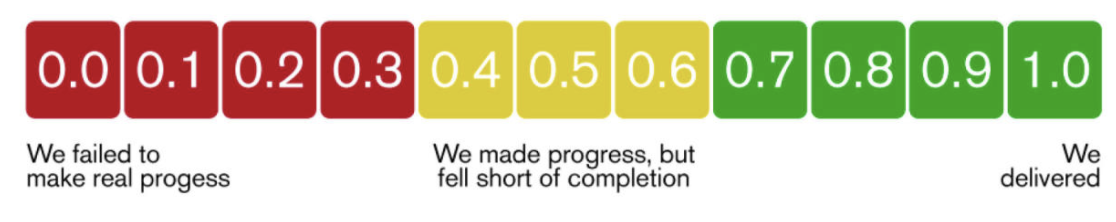

Finally, the OKR Framework suggests using a 0-1 scale for assessing the amount of progress made against key results at the end of each quarter:

- 1: All key results were achieved and, in some cases, even surpassed.

- 0.7+: Key results were mostly achieved, with some missing the mark ever so slightly.

- 0.4+: Some progress was made against key results but more work is still required.

- 0.1+: Very little progress (if any) was made against key results.

- 0: No progress was made whatsoever.

A few OKR best practices to keep in mind

In “OKRs Done Right,” product management coach Itamar Gilad calls out five OKR pitfalls that you should avoid at all costs:

- Using OKRs to express a plan (Output OKRs): The purpose of the OKR Framework is to set achievable goals that can be achieved in relatively short timeframes. It is not to build a full go-to-market plan that includes specific actions or product features. This framework isn’t a top-down business strategy. Each team must take full ownership for setting and achieving their stated goals.

- Developing non-SMART key results: As a reminder, SMART stands for Specific, Measurable, Ambitious, Realistic, and Time-Bound. Failing to adhere to these criteria will lead to the development of vague, ambiguous, lofty, or unrealistic goals.

- Creating too many OKRs: When it comes to OKRs, less is more. Trying to tackle too many goals reduces a team’s ability to focus on what really matters the most during a given quarter. As a rule of thumb, it’s a standard best practice to set three objectives, with no more than five key results linked to each objective.

- Creating top-down OKRs with no bottom-up buy-in: Top-down goals are typically less likely to get buy-in and support at the team level. This is because managers often lack the same level of perspective, knowledge, and insight of the team members ‘in the trenches’ who are actually doing the work daily.

- Leveraging OKRs for performance evaluation: While it may seem like a good idea in theory, doing so can sometimes trigger bad, unethical, or overly competitive behaviors within a team. This can quickly undermine a team’s productivity and ability to make a positive impact over the long term.

Suggested resources to master the OKR Framework

- A short but insightful introduction to OKRs by Ryan Panchadsaram and Sam Prince: What is OKR? Definition and examples

- A practical business case from Itamar Gilad, former Lead Product Manager and Head of Growth at Gmail: How OKR Helped Gmail Reach 1 Billion Users: an Interview with Itamar Gilad

- The Rick Klau’s speech that makes OKRs famous across the world: Startup Lab workshop: How Google sets goals: OKRs